Helping the Helpers

Reflective Practice as a Burnout Prevention Tool

This article is based on a presentation I delivered at the Complex Needs Conference (March 2025) in Naarm/Melbourne. The cross-sectional audience of this talk included people with lived experience of the criminal justice system and professionals from across the forensic, child protection and community service sectors.

This podcast interview coincided with the development of the talk. I’ve been energised by the conversations and actions that have followed.

Community psychology is a strength-based, prevention-focused discipline. So when it comes to a topic like burnout, it seems natural for my colleagues and I to ponder: why do we need to wait until people are already suffering? Can’t we design a service system where our staff thrive?

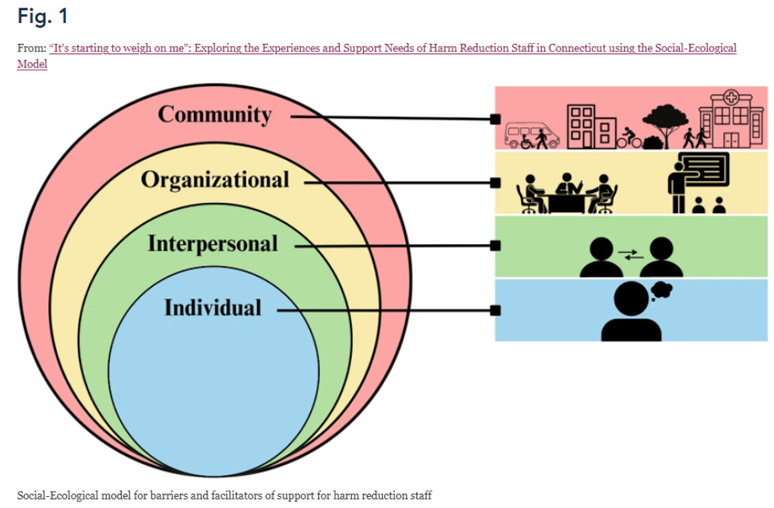

Burnout is a topic that polarises. Some believe an individual's coping mechanisms are the primary consideration, while others point to the system they’re marinating in. I suspect that it’s most useful to consider how burnout looks at both individual and societal levels, and each stage in between.

It's time to consider prevention rather than treatment. Staff are burning out at a rate that’s compounding difficulties for their service users, who rightfully expect consistent, predictable and trauma-sensitive care. If staff wellbeing and longevity are enhanced, then we could create a virtuous circle. In my experience as a practitioner, reflective practice groups can play a useful role.

Burnout is a form of exhaustion that rest alone won’t fix. Professor Gordon Parker, from the Black Dog Institute, describes it as a problem with our internal elasticity: we simply stop bouncing back in the way we once did.

Burnout gained legitimacy as a construct when the World Health Organisation (WHO) and their International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) classified it as an occupational syndrome in 2019. Three distinct symptoms are listed:

1. Exhaustion

2. Increased mental distance from one's job (cynicism)

3. Reduced professional efficacy

Gordon Parker and his Australian research team have identified a fourth domain: cognitive impairment – the mental fogginess that we experience when we're not as sharp as usual.

Some of the workplace conditions that lead to burnout are: high demand with low control, role ambiguity, high caseloads, emotional labour and persistent secondary trauma. Given that these conditions are well known, and replicated across business, neurobiological and psychology journals, why can’t we re-design job roles in a way that proactively reduces them? Burnout occurs when moments of stress (which can be energising) become chronic stress. Chronic stress impacts people's nervous systems, immune systems, and their relationships.

Efforts to prevent burnout seem best placed at the secondary prevention level. This differs from the universalism of primary prevention and takes into account that there are pre-existing factors in our service systems that see people at risk of developing burnout. Secondary prevention presupposes that with early intervention, and adequate screening (such as via the ProQOL), we can reduce the frequency and intensity of distress.

Think ‘Slip, Slop, Slap’ for social workers.

If 30% of the Australian workforce is struggling with symptoms (higher numbers in community services), then surely a large-scale initiative is warranted? Unfortunately, most of our current approaches don’t aim to prevent the onset of burnout, they instead react to existing symptoms. Common interventions include Employee Assistance Programs (EAP), discretionary leave schemes or shuffling staff between programs on a proverbial chess-board of chaos.

I caution against viewing our service systems as abstract flowcharts, as this can depersonalise matters. Aren’t we talking about people? Helping professionals? When folks are set up for success, they tend to thrive. Laziness does not exist, but harmful work environments do.

When people have been pushed too hard for too long, we start to notice wear and tear. In March of this year, ABC local radio had wall-to-wall emergency cyclone coverage for several days. The first story that was deemed important enough to trump this disaster in their running order was dire Victorian child protection statistics found within the 'Report on Government Services.' Public discourse in the following days focused on policy, parenting and perpetrators. Considerations of employee wellbeing and longevity were almost absent, aside from flippant references to ‘departmental inefficiencies’ and ‘staff turnover.’

Even if we quiet our bleeding-heart-do-gooder instincts, it makes good business sense to prevent burnout. Depending on their seniority, estimates for replacing a staff member range from between 50% to 200% of their annual salary. WorkCover premiums are also a pain point for organisations, with the more funding channelled that way, the less available for service delivery. Spending money on employee wellbeing reforms may not offer the PR-payoff that funding bodies gain with direct-to-client payment packages, but it’s worth considering how this type of expenditure could indirectly provide meaningful outcomes for service users.

A community needs analysis can have a dual purpose when considering workplace reform:

How ready is the sector to change?

Where are efforts best placed?

When pitching ideas ahead of a community's readiness to hear them, we risk fostering resistance rather than change.

When considering how burnout impacts our staff across ecological levels, I invite you to consider a case manager's role in Victoria’s forensic disability system.

· As an individual:

o They're a recent grad

o Their disposition is earnest and idealistic

o They value fairness and social justice above all else

· Interpersonally:

o They're often called upon by friends and family in times of need

o Their clients praise them when they go ‘above and beyond’

· At the organisational level:

o Their role has incredible ambiguity and an unknowable scope

o Their supervision sessions are infrequent and operationally focused

· At the community level:

o There are constant media reports about bail law reforms

o Politically there’s a bipartisan ‘Tough on Crime’ narrative

‘Self-care’ is not enough to help our case manager. In Jennifer Moss' excellent book on burnout from 2021, she lists the causes of burnout as: isolation, lack of fairness/injustice, favouritism, and a values mismatch between the worker and organisation. She states that "These root causes can't be solved by self-care alone. The ecosystem needs solving, and that’s not up to one individual to fix.”

The types of burnout experienced by our frontline community sector staff differ slightly from the high-flying corporate and legal manifestations that we often see profiled in (generally American) books. My experience in the sector is that these presentations are caused less by individual personality traits alone, and more by how these traits interrelate with workplace culture and processes: So, you're perfectionistic? Here's some intergenerational trauma to fix. Never mind, you're conscientious? Try to keep up with this admin avalanche. Dutiful? Here's an even bigger caseload.

Burnout festers when a job has ambiguous expectations, a high level of demand and a low degree of control. Staff are in this work for values-based reasons, so when organisational values appear to be drifting, we shouldn’t be surprised when this is a despairing experience - particularly for the young, idealistic professionals that the work attracts.

I want to consider how reflective practice groups can address the moral distress that staff feel in our service systems. At their best, these groups energise, provide connection, and increase people’s perceived effectiveness. They directly address burnout symptoms.

My interest in burnout comes largely from a theory and practice perspective, and my interest in reflective practice sessions is primarily as a facilitator with hands-on experience. I hold several of these groups a month, and at one point in 2021, I was facilitating seven-to-eight of these groups per fortnight.

In late 2020, I started working with a leadership team on ways to improve their cohort's wellbeing. I tried to integrate Professor Isaac Prilleltensky's work, focusing on their sense of mattering and ensuring that they felt valued. Through this process, I noticed that staff weren't getting these types of needs met from a centralised, top-down edict; they were meeting them through team cohesion and belonging – largely during their only time together each fortnight in these groups.

Group reflective practice sessions offer staff somewhere to build their competence and confidence, to reduce their professional isolation, to validate instances of moral distress and to problem-solve professional dilemmas together. I get constant feedback that these spaces work (and I'm continually hunting for evaluation tools to best capture this).

Why does burnout need to be a rite of passage? Isn’t it worth trying to reform our programs for both person-centred and financial reasons? Some well-designed community needs analyses could help us target ways to reduce its frequency and intensity.

Burnout prevention is complex and multifaceted, and reflective practice groups are one part of a wider solution.